Let’s imagine a scenario where a densely populated city—is actually a huge solar energy harvesting ecosystem. Well, this is what a handful of scientists and technology start-up companies are working hard to achieve in the near future.

Petronas Twin Towers

The Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia are the tallest twin structures in the world.Flickr/Hadi Zaher

Solar cell research has boosted panel efficiency over time. Today, scientists and investors agree that the true advantage of utilizing solar energy’s full potential—is to expand the amount of real estate that can be outfitted with solar, by making cells that are nearly or entirely transparent.

The countless variations of glass that lines the walls of skyscrapers and office buildings in large cities offer an important potential for such a technology, one that could transform these windows into solar energy panels. By engineering the window’s coating to capture sunlight and convert into electricity, the building could become self-sustainable.

Meaning that this produced energy could be used to power the building’s lighting system, run the computers, and best of all, fire up the air conditioning. This—is what transparent solar cell technology is all about. Currently, a few start-up companies want to bring this technology to the market—as soon as possible.

Making sense of transparent solar cell technology

The idea of the existence of a transparent photovoltaic cell is virtually impossible. This is because solar panel structure is designed to generate energy by converting absorbed photons into electrons.

For a material to be fully transparent, light would have to travel uninhibited to the eye which means those photons would have to pass through the material completely (without being absorbed to generate solar power). Previous claims toward transparent solar panels have been misleading, since the very nature of transparent materials means that light must pass through them.

“The real challenge is whether you can get the cost down and the electricity generation up,” says Sarah Kurtz, a scientist with the U.S. government’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Colorado. “There are lots of different schemes and strategies, and creativity will be the name of the game. If you can get the cost to the place where windows don’t really cost any more than conventional windows, it obviously makes sense to go ahead and have your windows generating electricity.”

Quite a few different types of technologies have been announced that claim to be described as solar windows, in the past months. Although none of these technologies have actually hit the market yet, there are a few worth a notable mention and special attention. One of such is the technology—in development—by expertise from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and from Michigan State University.

Technology from Solaria

Solaria is targeting its technology for windows that will be installed in newly constructed buildings. The company says its technology may provide from 20 percent to 30 percent of a skyscraper’s energy needs, depending on the number of south-facing windows that actually receive sunlight.

“If you look at the glass that’s manufactured worldwide today, 2 percent of it is used for solar panels; 80 percent of it is used in buildings. That’s the opportunity,” said Suvi Sharma, CEO of solar panel maker Solaria.

Solaria uses existing photovoltaic cells and slices them into 2.5mm strips. It then sandwiches those thin photovoltaic strips between glass layers in a window. “The way human eye works, you don’t even notice them,” Sharma said.

Technology from Michigan State University

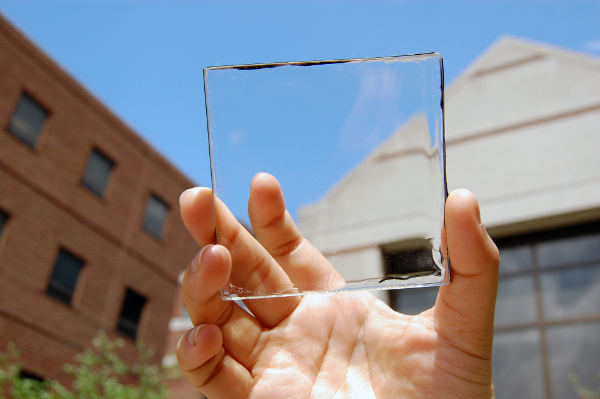

Scientists from Michigan State University have unveiled a fully transparent solar concentrator. A prototype, which allows visible light through and uses organic molecules to guide ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths to the edges of the glass, where tiny photovoltaic cells turn the non-visible light into electricity.

Due to the low conversion efficiency of this prototype and method, the research team figured out a new method to absorb wavelengths of light that are already invisible to the human eye. By simply focusing on creating a transparent photovoltaic cell, these researchers were able to harness the power of infrared and ultraviolet light.

Technology from SolarWindowTM Technologies

SolarWindow’s technology is based on organic photovoltaics, with varying color and transparency. Because it’s based on a photovoltaic thin film, it can be adhered to existing windows or incorporated into manufactured products relatively easily increasing its ease of integration.

“Rooftop space available for conventional photovoltaics is so limited it is difficult to generate meaningful energy for a skyscraper,” says John Conklin, the start-up’s CEO. “SolarWindow, on the other hand, is developing its transparent electricity-generating coatings for the vast surface area of glass available on a skyscraper.”

Solar power with a view: MSU doctoral student Yimu Zhao holds up a transparent luminescent solar concentrator module. Photo by Yimu Zhao.

Looking towards future applications of the transparent solar cell technology

“It’s a whole new way of thinking about solar energy because now you have a lot of potential surface area,” says Miles Barr, chief executive and co-founder of Silicon Valley start-up Ubiquitous Energy, a company spun off by researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Michigan State University. “You can let your imagination run wild. We see this eventually going virtually everywhere.”

But skeptics to this technology do not agree with this statement. “The optimal installation for solar is you want it to be facing south, you want a slight tilt to it, and you want good solar access, so you don’t want anything to shade those panels,” says Shiao, a senior analyst at GTM Research, a market analysis group in Boston, Massachusetts. “The problem with skyscrapers is suddenly you’re putting them in vertical orientation, there’s only one south side to the building, and chances are that skyscraper is next to another skyscraper, which is going to shade that side of the building.

These and many more challenges make experts skeptical about the solar window technology. “There are a lot of technical and design challenges, which quite honestly aren’t going to be fixed,” Shiao says. “It doesn’t make sense almost at any cost, unless you’re getting the panels for free or something, to really install that system on those big structures.”

Comments